"Art is a kind of illness."

Where do I start when I talk about the effect of AIDS on Art? For many of you reading this AIDS has always been a part of the social landscape; an accepted (unacceptable) risk of sexual intimacy. But I can remember when it wasn’t. I can remember the time before Death and Sex became domestic partners. The reaction to the introduction of AIDS was seismic. There is still the haunting question: How can the very agents of Life (childbirth, breast-milk, lovemaking, and blood transfusions) be so duplicitous as to hold the door open for Death?

Sex and Death have often been married in art themes. The most pervasive being the religious theme that mortality is the byproduct of carnality. Yep, sex makes death. Original sin: Eve eats an apple. She gets wise and sexy (and so gives Adam a taste of her sweet apples) voilà, Death comes to the party. Second most popular Sex/Death theme is that beauty is fleeting. (See any painting entitled “Death and the Maiden.” There are quite a few.) If beauty is fleeting, you better fuck it quick before it’s gone.

These questions take on new depths and imperative when the Artist is him/herself dying and knows it. An artist with AIDS is chronicling not only the journey of those who went before but the path s/he must tread. This article is not meant to be a verbal square in the Names Quilt. I chose a diverse sampling of artists living and dead, with HIV and without. What they have in common is the AIDS epidemic shaped and informed their work and their work healed, shaped and chronicled the affected communities.

The Heart Torn Open

In comparing the Art creating during other global devastation by disease, such as the Black Plague, I came across a phrase that stuck with me: “The heart of the art world was torn open.”

Youth, talent, genius...all lost. The art and artists that follow in the wake of such devastation are chronicling not only their own personal losses and our cultural loss, but the rejection or acceptance of their own deaths. Edvard Munch’s sequel to his own “Death and the Maiden” painting is called “The Kiss of Death.” In it, the maiden appears unmoved by the skeleton’s kiss. Like the artists we turn our focus on for this series, she seems to say, I may be taken, but never conquered.

Outsider Art

“On three counts I am an outsider: in matters of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for.” —Rotimi Fani-Kayodé

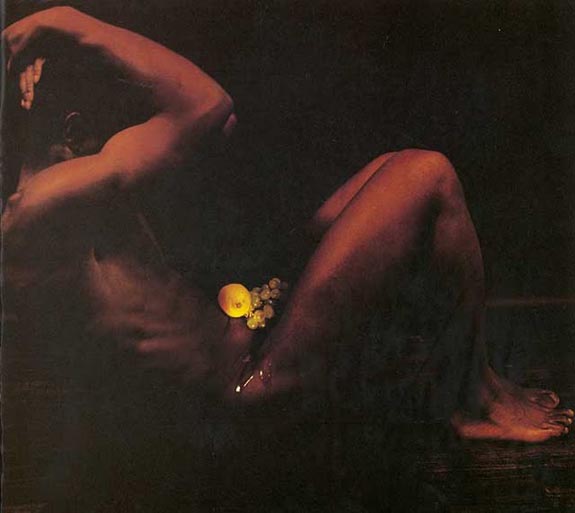

Photographer: Rotimi Fani-Kayodé (1955-1989)

Picture by Rotimi Fani-Kayodé

Born in Nigeria, Rotimi Fani-Kayodé and his family were refugees who immigrated to Britain. Fani-Kayodé was a founding member and first Chair of Autograph ABP, a charity that works internationally to educate the public on photography, with an emphasis on issues of cultural identity and human rights.

]

Provocative, seductive, intensely personal and politically engaging, Fani-Kayodé’s work is pivotal in British photography of the late Twentieth Century. Fani-Kayodé often collaborated with his lover, British photographer/filmmaker Alex Hirst (who died in 1994). Together, they created a photographic series entitled “Bodies of Experience,” and also produced the book Black Male/White Male, with Fani-Kayodé providing the photographs and Hirst supplying the text. The book was seminal in creating new examination of race and masculinity, and gains further historical significance for its raw portraits of famous queer men of color, many of whom, like the writer Essex Hemphill, also became casualties of the AIDS pandemic.

“Both aesthetically and ethically, I seek to translate my rage and my desire into new images which will undermine conventional perceptions and which may reveal hidden worlds. Many of the images are seen as sexually explicit—or more precisely, homosexually explicit. I make my pictures homosexual on purpose. Black men from the Third World have not previously revealed either to their own people or to the West a certain shocking fact: they can desire each other.”—Rotimi Fani-Kayodé

Fani-Kayodé was out as an artist and as a person living with AIDS. His sexuality, spirituality, cultural duality, and illness informed and directed his work. His photographic series “Ecstatic Antibodies” integrates “the technique of ecstasy” practiced by Yoruba priests in order to “ritualistically” transform imagery of black men.

“Nothing to Lose” by Rotimi Fani-Kayodé

Fani-Kayodé’s parents, forced to leave Nigeria as political refugees in 1966, were from a family who held the traditional title of Keepers of the Shrine of Ifa, the oracle. In the “technique of ecstasy” the priest in a trance communicates with the deity. Fani-Kayodé and Hirst held the view that the artist needs to establish a similar relationship with the unconscious mind.

Her Angelic Rebels

I will die but that is all I shall do for death.—Edna St Vincent Millay

Photographer/Performance artist: Tessa Boffin (1962-1993)

A founding member of the London-based AIDS and Photography group, Tessa Boffin is

]considered the first British lesbian artist to produce work in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

]considered the first British lesbian artist to produce work in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Boffin curated the traveling exhibition “Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology,” and co-edited the accompanying book, Her Angelic Rebels: Lesbians and Safer Sex (1989), which remains one of the most important photographic artworks to address AIDS from a lesbian perspective.

Prolific and sometimes controversial, Boffin used her art to move sadomasochism, gender fluidity (specifically queer gender-fuck) and other marginalized practices out of the closet and into the larger queer culture.

In 1991, she co-edited Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, the first collection of its kind, that advanced the visibility of lesbian photography to a new level. In the accompanying commentary, Boffin writes that she wants to place herself and her fantasy figures “into the great heterosexual narratives of courtly and romantic love: by making the Knight’s Move—a lateral or sideways leap.”

Her work, success and emerging fame as an artist, were not enough to satisfy her. Boffin took her own life in October 1993.

Sinking…Metaphorically

Sculptor: Robert Gober (1954—present)

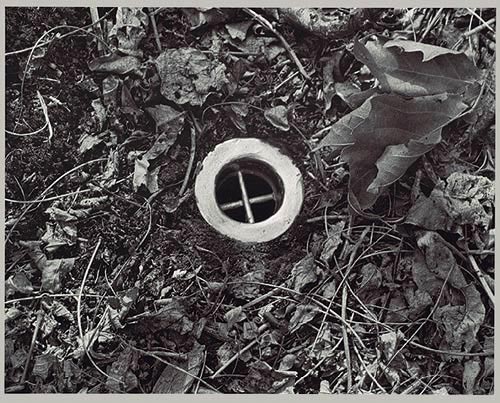

Born in Connecticut, Robert Gober studied art in Rome and was one of the premier artists to champion a return to figurativism in the 1980s. While Gober’s sculptures often have the appearance of “found art” i.e., everyday objects such as sinks, cribs, baskets, dog beds, arm chairs, newspapers and urinals appropriated as art; they are actually handmade, labor intensive and created of surprising materials.

It is more complicated to ascribe political (and AIDS related) meaning to a sculpture of a sink than to the photograph a man takes of his dying lover. We must often rely on artist statements, interviews and analysis of their lives or influences to accurately interpret the symbolism intended.

While Gober has been open about the way his homosexuality impacts his art, he remains a very private man. He speaks of his work and their relationship to dreams and memories. Gober refers to a recurring childhood dream of a room full of sinks with faucets open and water running: nightmarish, surreal while simultaneously domestic and familiar, and categorizes his work as his “psychological furniture.”

Some pieces lend themselves more easily to analysis than others. Gober created “Subconscious Sink” (1985), as a good friend was dying of AIDS. There are no faucets or drains, and no working parts—only a gaping hole at the sink’s bottom. The sink is useless—yet overwhelming. Critics have posited that its symbolism suggests cleansing rituals, although, with no running water, there is no ability to wash clean or purify. The metaphor of the “Half Buried Sink,” in which a white slab of mock porcelain appears like a headstone above a grassy grave mound, is transparent enough.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, I saw part of the series of “sinks” that Gober had created. The scope is something that pictures of the sculptures can’t give you. Floor-to-ceiling walls of painted jungle and the sound of running water like a distant brook or waterfall, and when you turn the corner, there is a sink, small and disconnected. The sense of alienation is overwhelming—of how we have captured something wild and essential, and trapped it into the dirty pipes for later convenience.

In other works, Gober employs fragments of the human body to suggest eroticism but also vulnerability and loss—major concerns for artists working at the height of the AIDS crisis. Faceless people only in pieces. Candles sprout from legs. A single trousered leg grows out from the wall. In another sculpture, the leg emerges from between a legless torso. Emerging from the womb? Or an ass?

Gober’s work is open to—in fact, demands—interpretation and speculation. And like so much of life, the truth of it remains to be felt rather than explained.

Tomorrow, "Art in the Blood" continues with poet Essex Hemphill and Israeli singer Ofrah Haza.